It's not enough to look to see.

If you look at shiho nage and kaiten nage from the outside, you see two completely different movements. And it's true that the outward form taken by the technique, the effects of the technique on uke, show things that have nothing in common.

So what does the equality in the title of this article mean?

Well, that different effects can be generated by a single cause, and that this single cause, even if it's not apparent at first glance, remains the essential thing.

What is equal in fact, what is constant in the two techniques called shiho nage and kaiten nage, is not uke's throw, it is - if we can see it - tori's identical movement in every respect, which results in two different throws. The video shows this:

So what's happening today in the teaching of these two techniques?

We see that practitioners are being asked to adopt different movements depending on whether they are doing one or the other technique, to modify the kaiten nage movement in order to do shiho nage.

Let's go back for a moment to the main strokes of kaiten nage, of which there are three:

- Opening of the front of the body in hito e mi under the effect of the rotation of the central axis of the body,

- Deep entry of the rear leg (irimi) in continuity with this rotation and opening, with the arms rising shomen,

- 180° rotation and deep backward withdrawal (tenkan) of the leg that had initially opened in hito e mi, the arms descend shomen.

These three beats, combined with the rise and descent of the arms in accordance with the cut of the sword (te katana), cause uke to fall awkwardly between tori's two feet. Nothing more needs to be added to the kaiten nage movement.

However, in order to enable uke to fall forward more easily, tori is asked not to throw uke when he should normally do so, i.e. at the moment of the tenkan withdrawal of the leg. Instead, he is asked to advance his rear leg in order to throw straight ahead, in an unnatural4th time. This is merely a training convention that has no necessity in the reality of the movement.

For shiho nage, the movement should be exactly the same, but we teach it in a truncated version of these three beats. Strokes 1 and 2 are indeed the same, but the third stroke is respected only up to the 180° rotation, and its last part is amputated: the final withdrawal (tenkan) of the leg towards the back is omitted.

There's a reason for this, and it's the same as for kaiten nage.

When the shiho nage throw is performed with this leg withdrawal, the fall is violent and can be dangerous for the neck (it is martially designed for this). To avoid any danger in training, we have therefore adopted the practice of forbidding tori to withdraw his leg in tenkan at the moment of throwing, in the last part of the movement, and to throw just as he has reached the end of the 180° rotation, i.e. in hanmi.

In this way, as in kaiten nage, uke retains the possibility of falling comfortably, and training is safe. Trauma is avoided.

This is all well and good, but it is a teaching of the Tao that the best things from one point of view can have harmful consequences from another. And a problem has arisen from this secure practice: because of it, knowledge of the true technique has been lost, as well as understanding of the relationship between the kaiten nage and shiho nage techniques as regards tori's movement. We have become accustomed to seeing these as two different techniques.

Yet the relationship between these two techniques is much more than a vague kinship based on similarities of detail; on the contrary, it's a true identity. And it is identities of this kind that enable us to understand the intimate relationship between Aikido techniques, which in Japanese is called riai.

Furthermore, the habit of throwing uke in shiho nage without taking the last tenkan step anchors in the body the reflex to cut in hanmi. However, as demonstrated on this site, no Aikido action is performed in hanmi. Hanmi is the position that precedes the Aikido action, but this position is not appropriate for the moment of the action, which is always performed on the dynamic support of kenka goshi.

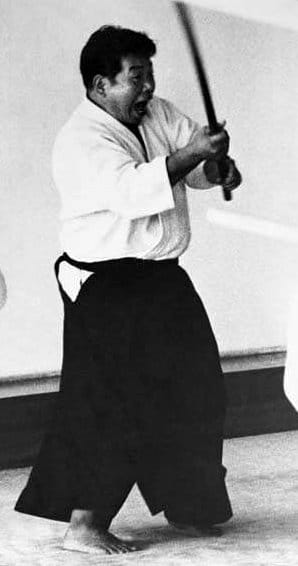

The photo below of Master Saito, taken at Tokyo's Hombu Dojo in the 60s, when he taught aiki-ken and aiki-jo at O Sensei's request, should convince the most recalcitrant of his students that - outside the very specific domain of the method - it is kenka goshi that is found at the moment of action, and not hanmi :

Shiho nage, of course, is no exception to this rule: the throw is carried out in kenka goshi, as in kaiten nage. Forcing the body to cut in hanmi goes against Aikido principles.

Last but not least, deleting the tenkan part of the tai no henka movement (also known as tai no tenkan) prevents you from completing the spiral of shiho nage. This stop in the movement forces you to cut into hanmi in the opposite direction of the spiral. Interrupting the spiral of an Aikido movement in this way, only to start again in the opposite direction, thinking that this is a normal way of executing the movement, is a serious incoherence, a major obstacle to understanding the principle of unity of each movement, which requires that when a spiral has started it should reach its end. It is a disaster in terms of the cohesion of body and mind. In this way, we're training generations of practitioners blind to the fundamentals of Aikido, and one day we'll have to repair the damage caused by these aberrations.

Today's watered-down Aikido has the flavour of irrational gymnastics; it's popular because it's sweetened and we like sugar, but there's nothing left of the natural taste, and it's no longer Aikido. To find what you're looking for, you have to know what you're doing.