When I started Aikido, we used to hear this little phrase about the ikkyo omote technique: "Push (the elbow) towards (uke's) ear ". And we tried to follow this instruction without really understanding why it was necessary to push up to the ear.

The reason is biomechanical: when tori twists uke's elbow upwards in the direction of his ear, it's the underside of uke's forearm that comes up for grabs. The video explains this:

In this situation, the hand of the forward hip can grasp the underside of the wrist, while the hand of the rear hip firmly holds the back of the elbow, in line with the olecranon stop (the olecranon is the upper end of the ulna that comes up against the lower end of the humerus, thus limiting the extension of the arm). When the forearm is so grasped and turned over, there are two effects:

1- Uke's shoulder is thrown forward, and he is unbalanced in that direction as a result,

2- The pressure on the olecranon is optimal thanks to the leverage provided by the rotation of the two hips in complementarity (a leverage which is impossible to obtain with a bad grip).

If the ikkyo technique is then applied martially, the result looks like the image below. There is a fracture of the olecranon, possibly displacement of the radius (3) and ulna (2), or even fracture of the humerus (1):

None of this sounds very attractive, but it's important to understand that this is what the ikkyo technique is designed for, not to gently bring an opponent to the ground. If you take uke to the ground, it's only because it's obviously not possible to break your training partner's arm.

It is therefore totally misunderstood to attempt to resist ikkyo during training, and thus transform practice into an absurd test of strength. Two of my students found themselves in this situation, and one of them almost lost the use of his arm for ever, which was only saved after several operations.

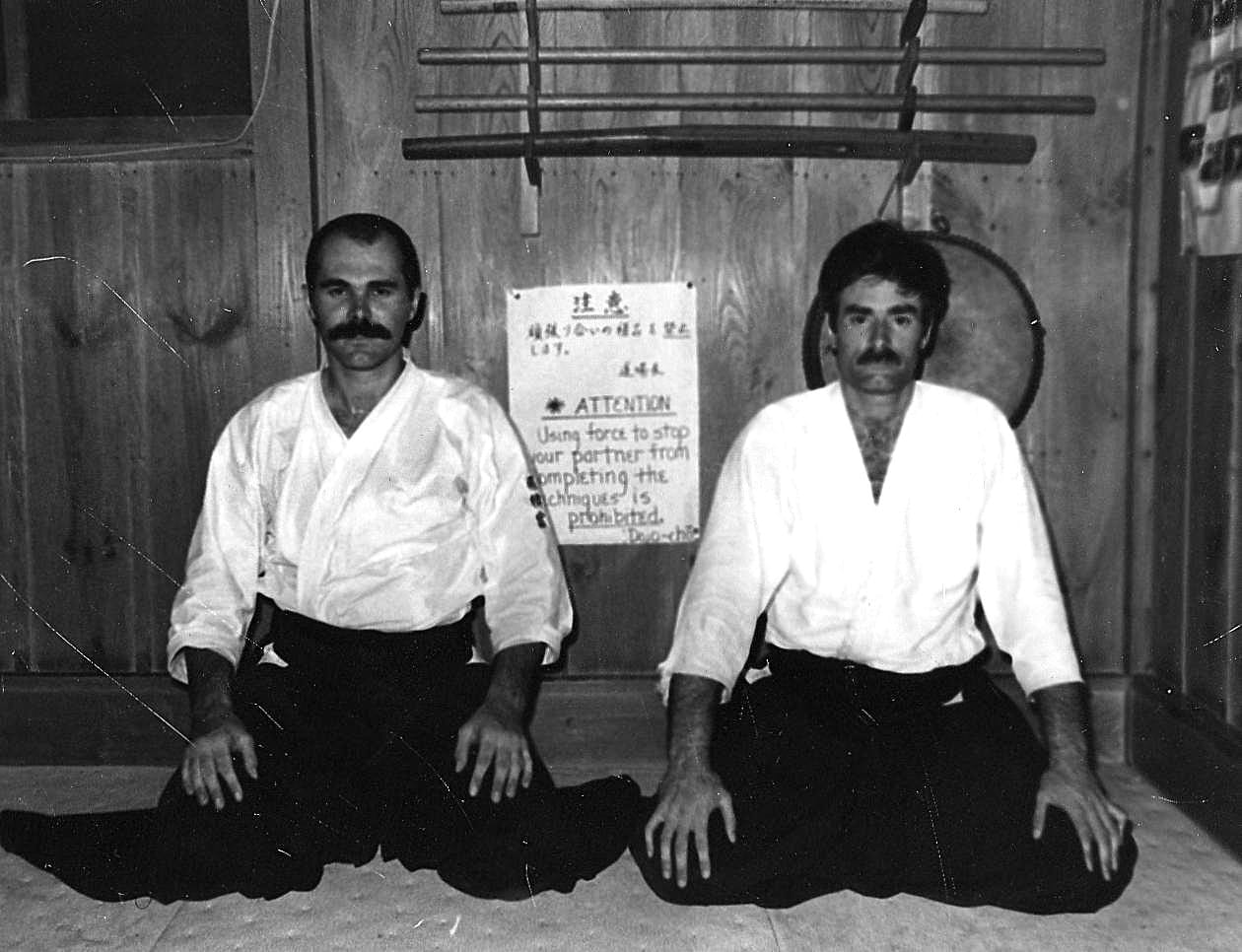

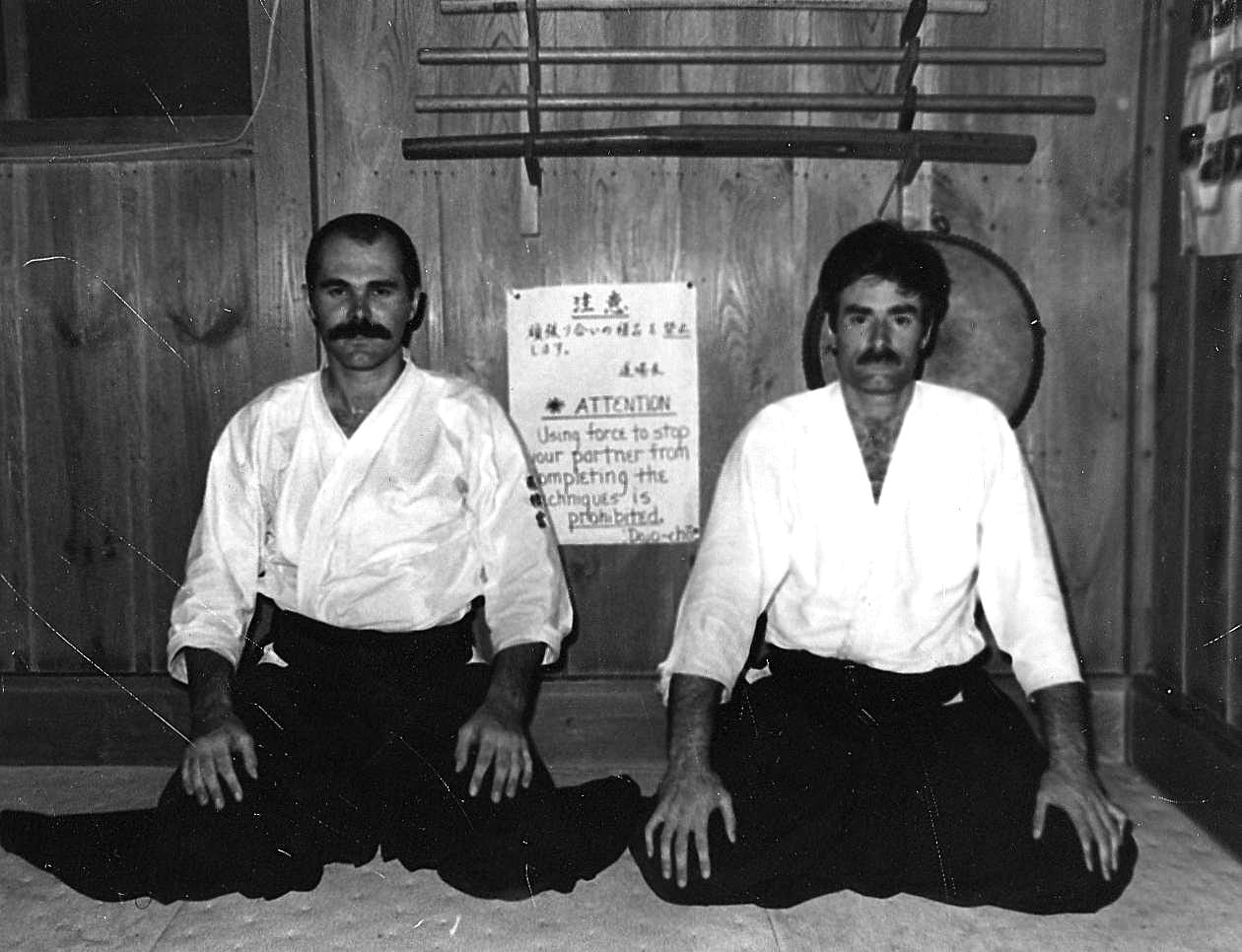

I've personally made all kinds of mistakes, including this one. In the summer of 1987 in Iwama, Master Saito got angry about the way Steven Solomon and I were practising. We were training precisely as I've just explained, blocking each other's techniques in a sterile and dangerous... stupid way. Master Saito then asked Patricia Hendricks, who was uchi deshi with us at the time, to translate the following warning for everybody's attention:

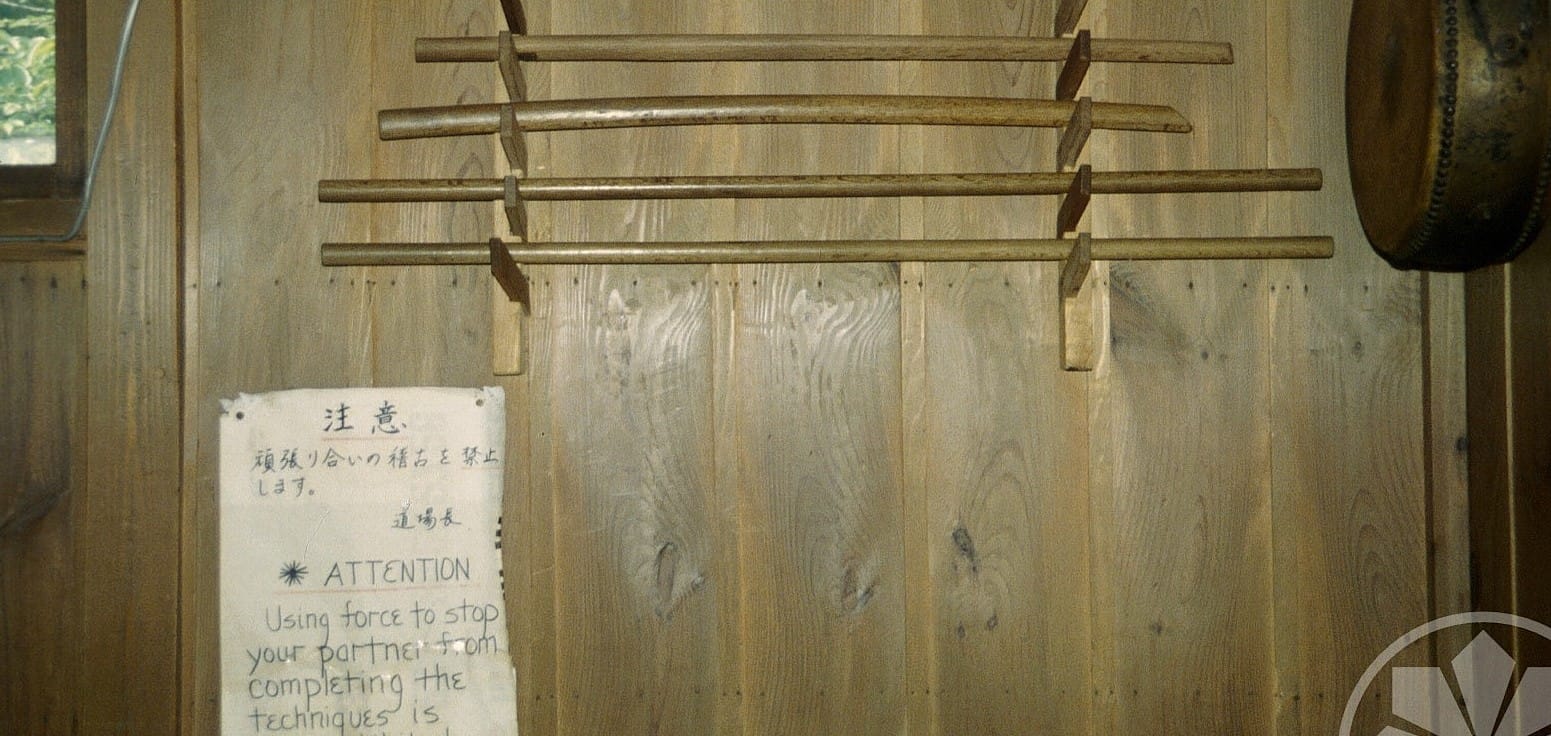

Steve and I took the photo above in front of the brand new poster, as a memory of this moment... that directive in the background, it was thanks to us that it was pinned to the wall of the dojo wasn't it? 🥴 I'm amused to see that it was still there a long time later... and that people still refer to it today:

You can't do anything other than practise ikkyo in a non-traumatic way, meaning in the form of an immobilisation, and that's fine. But there's a problem: if you train exclusively in this way, you end up losing sight of the fact that ikkyo actually allows you to throw an opponent with destructive power against another opponent coming at a 90° angle. This knowledge is essential to understand how the movement of ikkyo omote strictly respects Aikido's principle of irimi-tenkan rotation. If this knowledge is lacking, it will never be possible to understand why ikkyo ura obviously respects the irimi-tenkan principle during training, and why ikkyo omote does not seem to respect it.

What has been said here remains Chinese as long as the unique movement of Aikido is not understood, and that Aikido thus proposes a unique response to different situations. A unique response does not mean a unique technique though; there are 10,000 techniques, but the movement of the body is always identical to itself in all circumstances. In their multiplicity, the techniques of Aikido are born from this common origin, in accordance with the model of the universe where the multiplicity of beings is born from the One, from the division of the One.