When you want to answer certain questions seriously, sometimes you can only do so by opening up a horizon, and once again I choose to share with "TAIonauts" the untimely considerations to which Eric's question on YouTube leads:

"Hello, in suburi 7, you explain that following the tsuki, because of the orientation of the ken, the continuation can only be yokomen, perfect; nevertheless why in the kumitachi (at 3mn01 of the video) do you indicate shomen following your tsuki ??? Thank you."

Hello Eric.

That's a good point.

I didn't want to go into this explanation which is difficult and requires a familiarity that not everyone has with the principle of movement in Aikido. I didn't want to go into it... unless someone asked the question. You did, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity to say what follows, because - as far as I know - it hasn't been explained before. We're just going to have to hang on a bit.

Every attack is an opening, and if we don't attack in Aikido it's for this fundamental reason. Non-violence is a feeling that has been grafted onto this primary physical reason as an afterthought.

Yet what do the seven suburi of aiki-ken teach us... if not to attack in a straight line? Each of these exercises teaches us a way of moving forward, of going straight towards our opponent in order to bring him down with a deep forward lunge, whether with shomen, yokomen or tsuki.

So how can these linear attack exercises be reconciled with the principle of Aikido that has just been stated?

Well, it's very simple: uchitachi is not doing Aikido, suburi is not yet Aikido.

If Aikido does not attack, then Aikido cannot be found in an attacking exercise.

If the Saitos and Tamuras lost every time they attacked O'Sensei, it wasn't because they were less strong or slower than he was, it was because they were attacking, attacking using the attacking exercises that are the suburi, and thus allowing the Founder to respond with Aikido:

The Founder explained the vanity of any attack when confronted with the action principle of the universe.

However, this obviously does not prevent the attack from being carried out in accordance with a rigorous logic. One of the elements of this logic, Eric, is the one I underlined in the video and in the article 'Le juste geste' to which you refer: if I attack with tsuki, and then want to follow up with a forward slashing strike, I can only do so with yokomen. Shomen would be impossible in this context for the logical, physical reasons mentioned in the article, and this is why Master Saito taught suburi 6 and 7 with yokomen.

As far as Uke tachi is concerned, he is not placed in this context of attacking forwards, it's quite the opposite, he is attacked. This difference is fundamental, because in this situation he has the freedom to use the Aikido principle of action that is forbidden to uchi tachi.

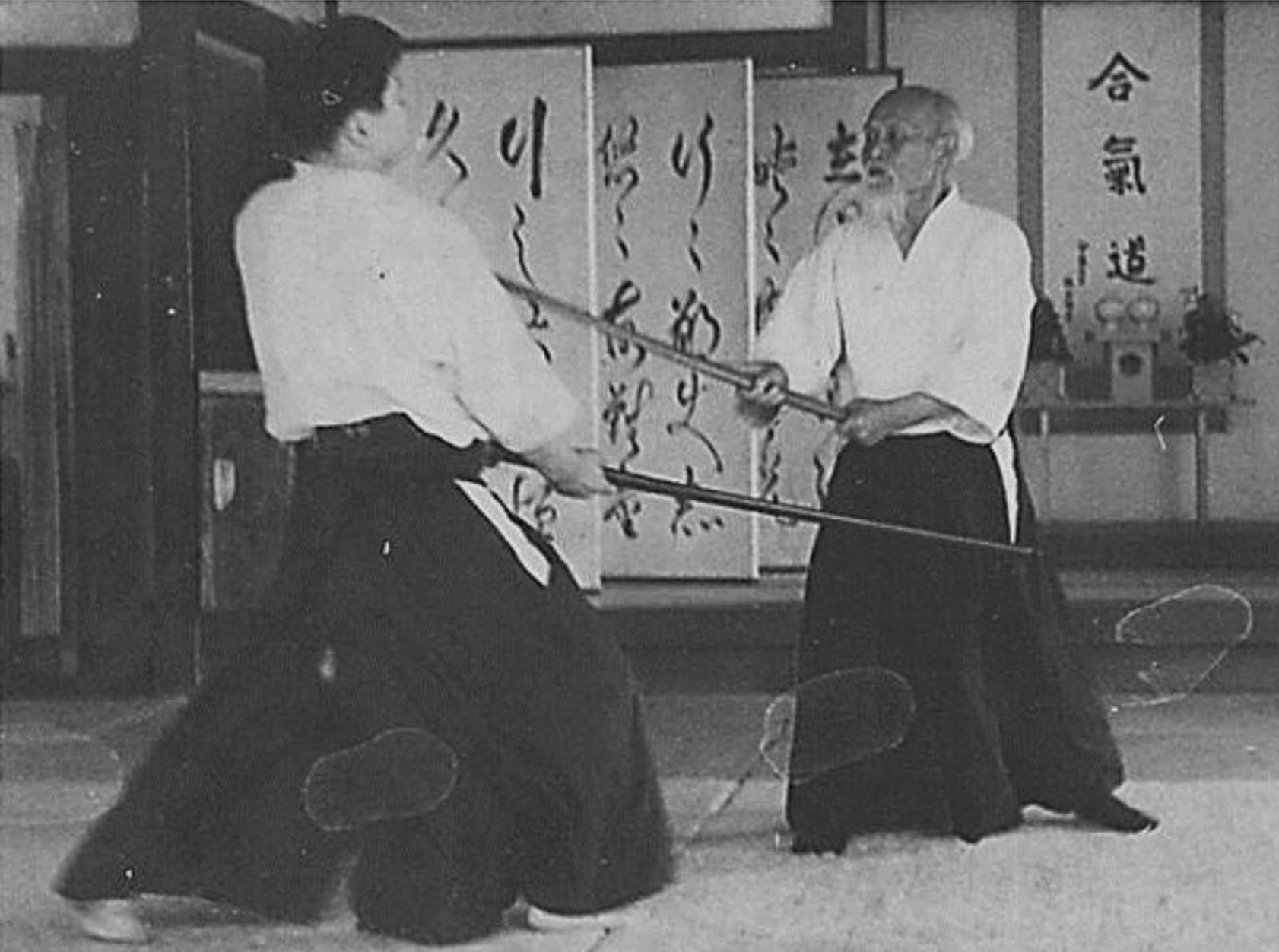

What does this principle say? That at the moment of the opponent's attack you must leave the hanmi position to strike in kenka goshi. This is what the Founder does in the photos and films we have of him; he is always in square at the moment he strikes and never in hanmi:

And now the difficult point.

In a simple situation - with a single opponent - uke tachi must resume his hanmi position immediately after striking in kenka goshi. The new hanmi position is shifted only by the angle of uke tachi's movement (we saw in the article "The rotation of the triangle" that this is how the triangle rotates).

But when he is subjected to simultaneous attacks from several opponents, uke tachi does not have the time to return to the hanmi position between each attack. This is what happens in the video to which you refer, Eric, between the tsuki in kenka goshi on the left and the shomen in kenka goshi on the right (because it is indeed a shomen).

There is also a new condition to be aware of: the kenka goshi shomen strike is delivered at 90° to the right of the tsuki strike, whereas in the suburi the yokomen strike is delivered in the same direction as the tsuki (the exercise is performed on a line).

These two differences are not without consequence.

As far as the first difference is concerned:

In suburi 7, the transition from a left front lunge to a right front lunge, in the same direction, forces the inversion of the hips at the end of a 180° rotation. This vast rotational movement drives the sword, which - because of its angular orientation at the start of the action - cannot do other than follow a similar path, in an inevitable oscillation from left to right, yokomen as we have seen.

But in the passage from kenka goshi on the left to kenka goshi on the right, there is no forward rotation.

There is only what we might call a tilting of the supports from left to right. In this very reduced passage, the sword is not drawn into the great spiral of the yokomen strike of suburi 7. This is why uke tachi can raise it above his head to take the jodan guard, without conflicting with a rotation of the hips (as would obviously be the case if one wanted to place a shomen after the tsuki of suburi 7).

As for the second difference, it's best to experience it physically:

Take a ken, Eric, and hit tsuki left in kenka goshi. Then start to raise the ken - with the inevitable angle due to the 45° orientation of the blade - as if you were trying to do suburi 7. But instead of pivoting forwards to do the suburi, pivot the axis of your body in the opposite direction, towards the back of your body, without changing the position of your supports. You will then realise that this rotation of the axis of your body towards the back, when combined with a 45° blade angle, naturally brings the ken vertical above the head, in jodan guard.

The need for the yokomen has disappeared; it is cancelled out by the difference between hitting the suburi 180° forwards and hitting it 90° backwards.

This reality is well done, if one may say so, since the jodan guard is precisely what is needed. Because uchi tachi can do nothing else in this context than attack with yokomen, uke tachi is then in a position to enter the latter's cut by bringing down his shomen, that is by using the major strike of the Japanese sabre.

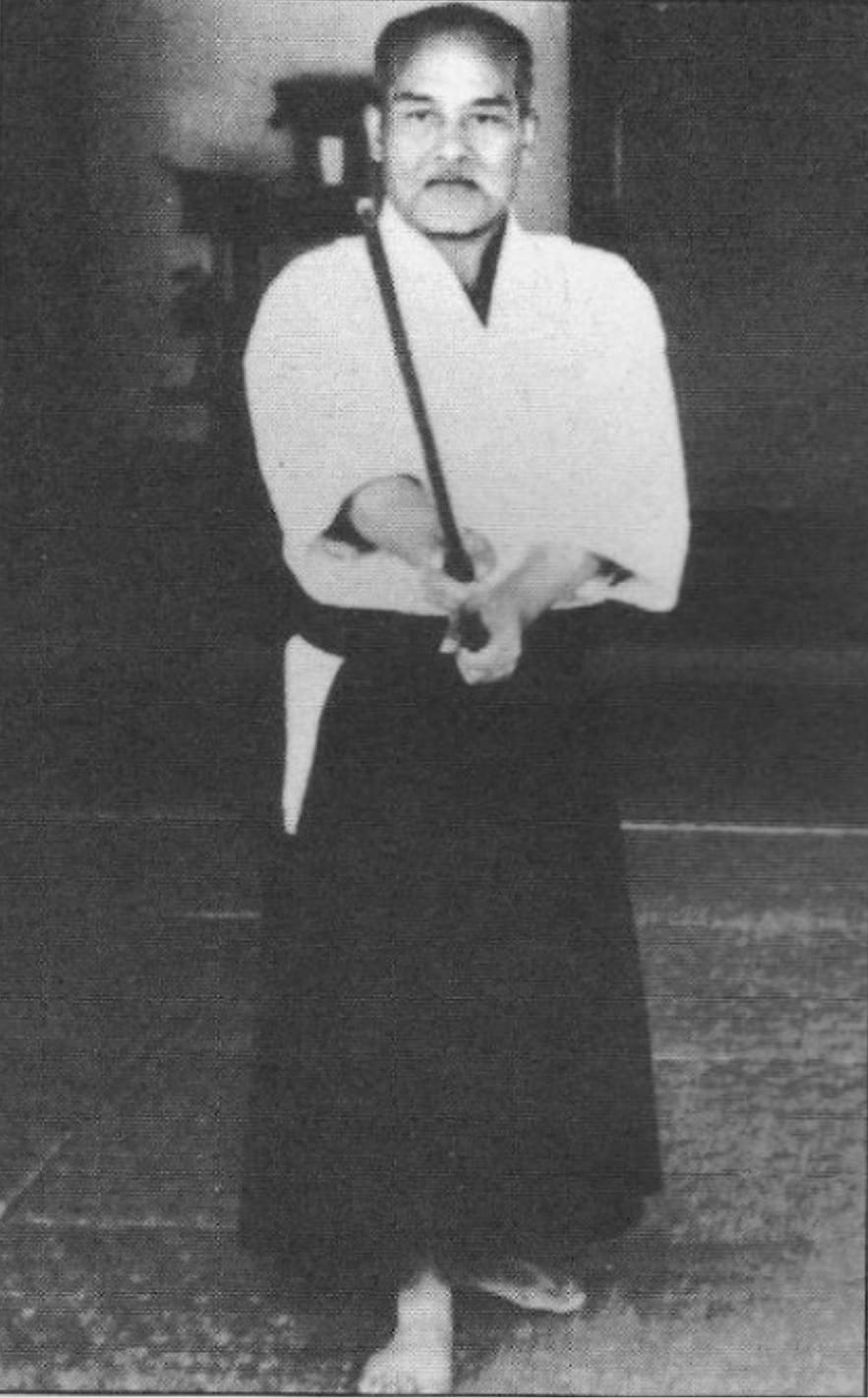

He does this with the feeling of power and tranquillity that the kenka goshi square confers in Aikido:

Shomen therefore to answer yokomen.

This teaching survived in the Aikido of the 70s, when I started. I don't know if it's still well understood or applied today, but it is indeed a necessity. Yokomen doesn't respond to yokomen, it's a law, and this is the fundamental lesson to be drawn from the two sword awase exercises in Master Saito's method (go no awase and shichi no awase).

If you look closely now, Eric, at the three photos I have used to illustrate this article, you will see that the attack using the suburi forces uchi tachi each time into a forward hanmi lunge. He cannot do otherwise.

On the other hand, you will see that O Sensei is never in hanmi when he receives this attack, but in square, in kenka goshi. It cannot be otherwise by virtue of Aikido's principle of displacement.

This shows that suburi reaches its limit here, and confirms that it is not strictly speaking within the scope of Aikido. It is only one element among others in a general preparation, a warm-up as I have already said.

O Sensei insisted many times on the fundamental nature of hanmi, but each time as a position.

This recommendation is generally explained by the fact that this position offers the least openings for attacks. This is true, but it's a bit short-sighted. The deeper reason for the hanmi stance is that it is open, not to attacks, but in all six directions (roppo), and thanks to this characteristic it alone allows you to move instantly in six different directions, which makes it the stance of the movement:

O Sensei posed for the photo above, but he never indicated that hanmi was in the action. Hanmi is nowhere else but in the hanmi position.

Of course we didn't understand this - me first - and for too long. We thought that everything in Aikido had to be done in hanmi. We were reinforced in this by the practice of suburi in line and in hanmi, which we obviously thought was Aikido. Removing the body was the key word! But the body in Aikido must not be removed, it must assert itself.

In the current context of Aikido teaching, where we continue - against experience and against the evidence - to train practitioners to cut in hanmi in all circumstances, I doubt very much, Eric, that anything I've said here will be of the slightest interest, and even less of any benefit.

But I have answered your question honestly.

Kind regards

Philippe