This article is a fiction, an imaginary intrusion into the conversation between Leo Tamaki and Guillaume Erard during an interview the latter conducted almost ten years ago, in 2015.

I entered this discussion through the window, inviting myself in without anyone's consent. I apologise for this rather tactless procedure, but he who wants the end wants the means.

My friend Gilbert is from Le Panier, he's a well-known figure there, he's inherited the twenty centuries of history of this district of Marseille. In the 1980s, when windsurfing was taking over the coasts of France, a colleague of his was teaching the sport in the Estaque area and asked him to replace him for a few days during a summer course. Luckily, there were piers and dykes on the harbour, and at the far end of one of these promontories was Gilbert, with his feet dry. The trainees who were tacking in front of him, obeying this voluble semaphore as well as the Mistral wind, had no idea that their makeshift coach was just on stage: in all his life he never set foot on a sailboard.

The impostor was friendly, he was helping out a buddy, he was selling wind, but cheerfully, this imposture was wearing the mask of a smile.

But there are impostures that don't make you smile.

I recently read Guillaume Erard's interview with Leo Tamaki.

I have nothing against Leo, in fact to some extent I find my own indignation in this young teacher, and some of the reasons that led me to leave the FFAB in 1990. So what prompts me to write today is not Leo's break with the federal milieu, whose objectives and methods I don't share any more than he does.

On the other hand, I am bothered by the tone of the interview, which is well captured in the title chosen by Guillaume Erard: ‘Youth at the service of the evolution of Aikido’. The interview suggests that O Sensei's art is adjustable, that people are free to modernise it as they see fit, and to choose the direction that suits their personal tastes, thus legitimising the founding of new schools.

In Japan, the warriors who founded their ryu at the same age as Leo rarely survived the challenges to their lives that such boldness earned them, but this kind of bickering disappeared at the same time the quarrelsome ronins were vanishing, and founding a martial school today no longer exposes you to the risk of violent death.

There is, however, a downside to this peace of mind, and that is that candidates for notoriety must now make their merits known in ways that have nothing to do with martial skills. The modern battlefield is that of communication.

The value of a martial art is no longer measured by the ability it confers on a man to come back from war alive; it is now measured by the media coverage achieved by the pioneers who built the art. And in an assessment of this kind, the techniques of the school itself are infinitely less important than the techniques of image and marketing.

The teacher is chosen on the basis of his position in the media: comments are what counts, both good and bad, because it's not the content of these comments that matters, it's the number of them. The objective content of the art has ceased to be an element of appreciation; it is no longer questioned, it is no longer tested, it is discussed.

Modern warriors discuss.

O Sensei's work was not in vain; the democratic discussion around the great Aiki brought people together under the same roof...

But chin-wag also brings people together in the pub, and ‘it turns a forger into a goldsmith’.

So I grab my Guinness, I leave the counter where I was drinking solo, and I approach the stove where you have your table my friends, I pull up a chair and take my place in the row of the chatterboxes, I too want to chat and commune in the chat, please accept that I change your duo into a triplet, and honni soit qui mal y pense.

Guillaume - Are weapons really necessary to learn Aikido? Even if they are, which ones should we use? O Sensei talks about Ono-ha Itto-ryu, Shinkage-ryu or even Kashima Shinto-ryu, yet in Aikido seminars we mostly see Kashima Shin-ryu, Katori Shinto-ryu or Musō Shinden-ryu. What does this have to do with anything?

Philippe - Nothing Guillaume, nothing. O Sensei may have practised some of these arts in his youth, but what he did afterwards with a sword, a stick or a spear was none of these anymore, it was Aikido. O Sensei's use of weapons has nothing in common with the use of weapons in these ryu, nothing. And if we have to answer the question of which of these schools of weapons will allow us to understand Aikido, the answer is: none.

Leo - Do you need weapons to practice Aikido? For me, under no circumstances. In other words, I think that the work of taijutsu can totally stand on its own.

Philippe - It's true, you don't need weapons to do Aikido, you do Aikido with weapons that's all, just as you do it without weapons, and vice versa, it's a whole. The whole cannot be divided, otherwise it's no longer a whole, there's no choice. What would you say, Leo, if I were to put your question the other way round: ‘Do you need taijutsu to do Aikido’, and if I were to say that the weapons work in Aikido 'can totally stand on its own ’? Would you then, perhaps, find that I pay little attention to unarmed practice?

Leo - My opinion is that the weapons work was O Sensei's personal work, and that he used it to underline certain principles, that it was used a lot for demonstrations, and that it was used as an exercise, as tanren, etc. I don't think he had in any way set up a structured system of weapons and I can't imagine that's what he wanted. But obviously that's just a guess.

Philippe - And I guess the Eiffel Tower is in Paris... When something is certain, it's not a sin to say it with certainty. O Sensei never set up a structured system of weapons: that is true. He never taught weapons according to a method: that is true. Morihiro Saito clearly said that it was he who structured the weapons according to a method, in order to better memorise O'Sensei's techniques which sprang up spontaneously without any reference point for understanding them.

But if you have to put everything into perspective, Leo, then it seems that O Sensei's transmission of empty-hand techniques was no more structured than the transmission of weapons techniques. And the technical hodgepodge that we find today under the name of Aikido is perhaps not unrelated to the less than didactic nature of the Founder's teaching.

‘Weapons work was O Sensei's personal work". I replace the word personal by the word specific and I say the same thing: it is true, and this specific work of O Sensei, distinct from any other, is called Aikido, and this specificity is precisely, Guillaume, what prevents us from understanding it in the light of other ryu, however respectable they may be in their own domain.

And of course Ueshiba used weapons as a tanren to express his art, like a painter uses a brush. But Leo, didn't he use taijutsu in the same way? What is taijutsu if not a tanren? The whole of Aikido is nothing other than a tanren; Aiki-do is simply a way of exercising and training towards Aiki. In this path, weapons and taijutsu are necessary means and tools, but none of them takes precedence over the other.

Leo - After that, if it's a personal taste, it's possible to make weapons and make developments. I've allowed myself to do things that are very pretentious. I've developed certain personal weapon forms because the existing ones didn't suit me and didn't correspond to the Aikido I was taught.

Philippe - This is typically what we call a youthful error: thinking that it is possible to arrange things to suit one's own ideas and fashion. I say it straight out Leo, because I made this mistake long before you did.

Aikido doesn't depend on us, Aikido forbids the ‘development of personal forms’, it is the principle that decides, not the man. And the principle doesn't give a damn about personal conceptions, or the opinions we may have, or the interpretations we may make. It demands, and anything that doesn't comply with its demands is wrong, that's all. What suits me, what doesn't suit me, one person's taste, another person's taste, all these considerations and moods around a belly button window are irrelevant.

Nothing comes from the individual, the practitioner is the vehicle of something greater than himself, something infinitely beyond him, and the only thing he can really provide is his neutrality in expressing the forces that run through him. It's not the vase, it's the void within it that holds the water.

Leo - I found there was no coherence. That's often what bothers me, the incoherence between the empty-hand system and the weapon system when you're picking up bits and pieces left and right. What I'd been taught didn't fit in with the taijutsu work I'd received [...] I'd picked up teachings left and right from the Iwama style, the Nishio style etc. from various teachers, but all that didn't correspond to what I was doing with my bare hands.

Philippe - Or perhaps these fragments collected here and there were too ambiguous. An incomplete mixture of uncertain elements gleaned from various schools is called syncretism, and syncretism is never a synthesis.

You're looking for coherence, you say, it's the synthesis that makes all the elements of a whole coherent in relation to each other, insofar as they are developed from a common origin.

Would you perchance have the idea of redoing alone, from the limited means that are yours if we compare them to O Sensei's genius, the synthesis that he devoted his life to perfecting, and which he called Aikido?

This synthesis is right before our eyes, the Founder left it for us, we must of course make it our own, and to do this we must follow in his footsteps, which is already difficult enough. But redoing the path from the beginning, discovering once again the path taken by a man of exception, it's as infeasible as it is absurd, it's like trying to discover once again Newton's laws by pretending that Newton never existed.

Guillaume - You talk about hitoemi, a position that is often used with weapons, do you use it in your Aikido?

Philippe - The approach that consists of questioning the relationship between weapons on the one hand and Aikido on the other only makes sense to a mind that considers that there are two different domains there, that weapons are on the left bank of the river and that Aikido is on the right bank.

But this is not the case Guillaume, the weapons of Aikido are not outside of Aikido, the weapons of Aikido are not something other than Aikido, and one cannot compare weapons to Aikido, just as one cannot compare backstroke to swimming, backstroke is swimming.

One of two things, then: either hitoemi belongs to Aikido and is used both in the practice of Aikido with or without weapons, or hitoemi does not belong to Aikido, and in this case can be found neither in the practice of Aikido with weapons nor in the practice of Aikido with bare hands.

It so happens that hitoemi is related to the movement of Aikido, and therefore, insofar as this movement is always identical to itself, hitoemi is necessarily equally important, whether Aikido is practised with or without weapons.

Leo - I use three postures: shizentai, hanmi and hitoemi.

Philippe - I also use shizentai, like everyone else, when I'm queuing at the post office. Careful Leo, "posture " is not far from imposture, Guillaume is right, it's the word position that's appropriate here. In a position, the human body is still, it stays for a certain time, it remains, it is in pause, the posture, on the other hand, flirts with posing.

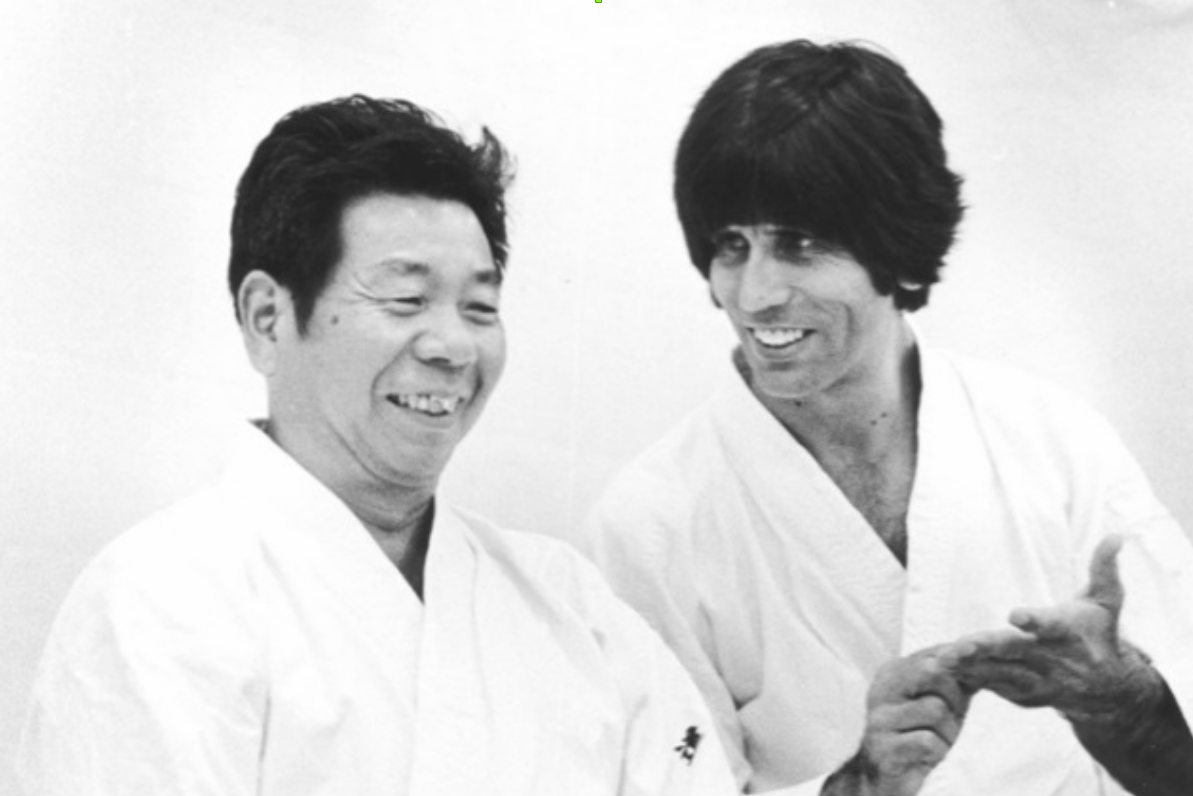

The shizentai position is that of a man standing with his feet shoulder-width apart. It is comfortable, as Master Tamura used to say, which is why it is used for angling and by the Queen of England when she attends parades, but it is nowhere to be found in Aikido.

It's true that O Sensei left shizentai out of his practice because this position offers more openings for attacks than a profile position. But it's a platitude to say that, and it's not enough.

Shizentai is absent from Aikido for a much deeper reason: it's because this position doesn't allow you to move immediatly in the six possible directions. The only stance that allows you to move instantly in any of the six directions (roppo) is hanmi, which is why hanmi was also called roppo in the past, when knowledge of this specificity had not yet been lost. The name hanmi emphasises the shape and presentation of the body in space when the feet form a triangle; the name roppo emphasises the six movements authorised by this triangular shape of the body, and which are subordinate to it. But fundamentally these two names describe the same thing.

The exceptional mobility of the hanmi position is a geometric consequence of the triangulation of the feet. Any position other than hanmi - particularly shizentai - prevents instant movement in the six directions. This is why O Sensei hammered home in his teaching that there should be no other position than hanmi in Aikido, he wrote this several times and in no uncertain terms, why not read it, why not listen to it?

As for hitoemi, of course it is of major importance, but it's not a position, it's a photograph of the body taken at a certain moment of its rotation, it's a freeze-frame of a moment of rotation: it's therefore a movement of the body, and a movement is the opposite of a position.

This does not mean, however, that movement and position are not linked. In military conflicts, we often oppose wars of position and wars of movement, but this is the wrong way of looking at things: movement and position depend on each other, and there can be no correct movement without a correct initial position. This is why the importance of hanmi is fundamental; the irimi-tenkan rotation of Aikido, whatever the angle at which it manifests itself, is only possible from the hanmi position: hitoemi is born from setting hanmi in motion.

We must never lose sight of the fact that breaking down a movement is certainly useful for understanding it better, but we must also remember that the phases broken down in this way are not positions, they are moments in a dynamic, moments artificially frozen for the purposes of teaching. When a photo ‘’immobilises‘’ a gymnast upside down in the middle of performing a back somersault, everyone understands that he is not in a position, but in the course of his movement.

Guillaume - The definition of hitoemi will depend on the ryu.

Leo - Very much so. I asked Master Tamura directly and he told me that there was no difference between hanmi and hitoemi. Which is not my personal opinion, mind you. As far as I'm concerned, these are two very different postures that are designated by two different and explicit words. But that was his thinking at the time I spoke to him about it.

Philippe - And he was a thousand times right Leo, what he was trying to make you understand is what I'm trying to say here too: hitoemi is only ever a fleeting moment in the rotational movement that starts from hanmi and returns to hanmi. You can't blame O Sensei for not being clear on this point.

I will try to use a different vocabulary:

Hanmi is movement insofar as it is still unmanifested, it is Aristotle's motionless motor, the prime principle. In the context of Aikido movement, it is therefore the stable and peaceful heart of the six possibles, which are there at rest but ready to unfold at any moment. The manifest is present in the unmanifest, it is only still not yet made manifest, and this is an important lesson that we can take away from Aikido.

Hitoemi is the way in which rotation opens the human body towards any of the six possible directions, at the very moment when hanmi is set in motion.

Kenkagoshi is the stage immediately following hitoemi in this setting in motion of hanmi, it is the moment of irimi, the moment of the strike, the moment when the feet, in the process of rotation, have gone beyond the still triangular phase of hito e mi, to reach the square phase where the power is delivered.

Hitoemi and kenkagoshi are the transitory forms taken by the body when the movement that is still only potential in hanmi suddenly manifests itself. The irimi-tenkan rotation brings these forms out of hanmi for a brief moment, and they return to it as soon as the rotation is complete.

From hanmi to hanmi then, as O Sensei explained.

If Master Tamura told you that hanmi and hitoemi were the same thing, Leo, it's because there's only one difference in modality between these ‘two’ which are in truth the same reality; this difference in modality is that which there is between stillness and movement. Tamura knew this, he told you this in his own way, but your mind remained trapped in words, words that were for you ‘different and explicit’.

Leo - In hitoemi your hips go on the line, so you occupy the smallest possible surface area. This is an important point in many weapon movements. I almost never work with shizentai, which is very dangerous in this context and reserved for the greatest masters.

Philippe - I conclude from this that it is therefore reserved for the greatest masters to disagree with O Sensei, and incidentally with the universe, by not respecting hanmi.

As for considering hitoemi as a 'fixed position' (sorry for this pleonasm, but I'm hammering it in until I wear out the hammer), as for putting oneself in ‘ hitoemi guard ’ with a sword or a spear, this comes down to locking the knee by opening the front foot too much, this locking of the knee blocks the hips and prevents any mobility of the pelvis, and therefore any rotation of the body.

Yoshinkan students arriving at Iwama for the first time were unable to practise weapons; they first had to get rid of the 'hitoemi guard ’ that Master Shioda had taught them. I practised with one of them in Iwama, he was a fourth dan Yoshinkan, and he couldn't understand why he couldn't move with his sword.

Hanmi is the only guard in Aikido and the key to Aiki movement.

Guillaume - This is interesting because in Daito-ryu, unlike Aikido and its specific hanmi, we practice a lot in shizentai and the hanmi guard is discouraged. However, Aikido techniques come from Daito-ryu and we can wonder why O'Sensei made this change of guard. Ellis Amdur attributes Ueshiba's hanmi to his Jukendo experience.

Philippe - I think, like Ellis Amdur, that Master Ueshiba's experience of Jukendo and the spear naturally accustomed him to using the hanmi stance, and encouraged him to compare it to the shizentai stance in the techniques he learnt from Master Takeda.

This comparison revealed an extraordinary quality of hanmi which led him to completely abandon the shizentai stance of Daito-ryu and definitively adopt the hanmi stance, breaking with the art of his master in the process.

This change of guard was the foundation of Aikido. Without this break with Sokaku Takeda's teaching, Aikido would never have been more than an advanced form of Daito-ryu.

So yes, as you say Guillaume, we can wonder why O'Sensei changed his guard in this way. I would even go so far as to say that this is the heart of the debate and that the answer to this question is the key to what separates Aikido from Daito-ryu.

So I repeat here, at the risk of being tiresome, that the profound reason that led Morihei Ueshiba to replace the shizentai guard of Daito-ryu with the hanmi guard of Aikido, is related to a very remarkable quality of hanmi as far as movement is concerned: the hanmi guard allows instantaneous movement in the six possible directions towards the front of the body, which is why hanmi is also called roppo (meaning six directions). The shizentai guard does not allow this. Only the hanmi guard allows you to obtain six possibilities of immediate and safe movement when simultaneously attacked by four opponents. Only the hanmi guard allows you to throw your body in the ideal rotation of a spinning top (tai no henka), according to the irimi-tenkan principle of Aiki, in any of the six directions in a flash, without the risk of being hit.

A little test: how many teachers these days are capable of getting into the hanmi position and clearly demonstrate the six possible movements from that position in the context of a group attack?

Very few, I'm afraid, and until we understand in concrete terms how it's possible to move in the six safe directions from the hanmi position, we can't understand O Sensei's requirement to always adopt this position before the action, and to always return to it once the action has been completed.

This requirement appears several times in O Sensei's book Budo. And for my part, I'll always remember the image of Master Saito on his moped, one day when he was going shopping in Iwama: as he passed the field where we were training freely, he shouted to us with a smile ‘Hanmi, hanmi... hanmi!’, as if to say ‘don't lose sight of the essential’.

Leo - I use hanmi a lot. With that in mind, I think you have to be clear about your technical choices, understand that they're all choices, and therefore that your choice doesn't invalidate that of another. For me, the hanmi position is very important from the moment you start using weapons, but it's much less important when you're bare-handed. Indeed, from the moment you consider that Aikido can be practised without weapons, why put yourself in hanmi? If you don't do weapons work, for me it's absolutely not a necessity, and people who don't do weapons work because it doesn't interest them can reach the highest level of Aikido, and in my opinion don't need to use the hanmi position.

Philippe - By trying too hard to be consensual, we're killing common sense: I think the Earth is round, but other people think it's flat, ‘my choice doesn't invalidate someone else's’. Nonsense, the flat or round shape of the Earth is not the result of a choice, it is the effect of a reality. Physical science, which is the knowledge of this reality, has nothing to do with the opinions of some or others.

‘Why get into hanmi?’ Because if hanmi is the origin of the movement of Aikido, it is the effect of a necessity linked to human biomechanics, just as the shape of the Earth is a necessity linked to the laws that formed the universe.

Hanmi is not the result of a human choice Leo, nor yours, nor mine, nor even O Sensei's. Hanmi is related to a principle that runs through all of physics and is called the principle of least action, which means that no natural action can be shortened, as another Leo (Leonardo da Vinci) saw very early on. And nature doesn't choose to apply this principle selectively to stars and not to salads. The principle applies universally to all forms of existence, that's what a principle is, it's a fundamental link common to all beings in a whole, and around which they are organised (DNA for all living cells, if you like), the principle links together all the elements of the whole in question, without exception.

On the other hand, you think that hanmi is not essential, and you say, without laughing, that one can ‘reach the highest level of Aikido without using the hanmi position’. Allow me to remind you that O Sensei taught exactly the opposite of what you're saying. He wrote verbatim that all Aikido techniques must begin and end in the hanmi position.

This is not an opinion or a belief, it is a reality of nature, which can be verified and measured: hanmi is the necessary condition for activating the principle of least action for the movement of a man on the ground of this planet.

O Sensei saw this reality, which Takeda did not, and he organised all the techniques of Aikido - with or without weapons - on the basis of hanmi, because he was not free to choose. Do you understand, Leo, the meaning of this expression, you who think that you are free to choose the tools that suit your Aikido, like you do your shopping at the DIY store ?

Our freedom is exercised only within the limits imposed on us by our nature. To achieve what Aikido proposes, you are not free not to use hanmi at the start of each technique. This is not the dogma of some fanatic fundamentalist from Iwama or elsewhere, it is a reality, just as to live you are not free not to breathe.

Guillaume - One gets the impression that in Aikido everything should be done with weapons as with bare hands and vice-versa. What is your position on this?

Leo - Master Tamura once said something that I completely agree with. He explained that what must be common are the principles, not the forms.

Philippe - Hence the importance of agreeing on what we mean by the word principle, to which the forms are subordinate.

Some people will say shisei, kokyu, kamae, maai and so on. I agree that all these are very important, but they are not principles; they are necessary conditions for the correct implementation of the principle of action.

A principle, once again, is the primary cause of everything that is, in the particular sphere that depends on it. There cannot therefore be principles in Aikido; there is a principle, and then there are some conditions for its action.

The principle of least action in Aikido is called irimi-tenkan; it is the rotation of a vertical axis around itself (the One) which gives rise to the complementary interplay of opposites (the Two). In Aikido, the appearance of opposites is physically manifested by the two hips in complementary rotation around the spine, one always in the opposite direction to the other. This dance of yin (tenkan in Aikido) and yang (irimi in Aikido) is the origin of movement. All the rest, all the technical forms derive from it, and whether these forms are with or without weapons is indifferent, they will necessarily be in conformity, provided that they are authentically derived from the principle of single action, and from the movement which is its first manifestation.

It so happens, due to natural physical and geometrical constraints, that the first condition for the implementation of the principle of least action of the human body is hanmi, which is why hanmi is the specific form of kamae in Aikido.

Guillaume - Is nagare present in your teaching from the start?

Leo - Yes. For me it is present from the start because I am not really a fan of stopped work. We were talking about weapons earlier. Although Aikido doesn't really come from weapons, the Aikido that I do today is strongly inspired by weapons. As in other schools, giving them much greater importance than they had in the original Aikido is an evolution.

Philippe - In order to understand the ‘evolution " you claim here, I would need someone to explain to me the concept of ’original Aikido' in relation to which it is supposed to appear.

Because in all the photos of O Sensei, in all the films we have of him, as far back as we can go in time, he has a sword, a spear, a stick or a bayonet in his hands. This does not mean that Aikido comes from weapons - an idle and sterile question, arising from a false problem - but it does mean, at the very least, that weapons are present in the same way as taijutsu in the Founder's practice, at every stage of his life. The presence of weapons is therefore indisputable, from the early days of Aikido in the 1920s, when O Sensei definitively adopted the hanmi guard.

The fact that O'Sensei intensified his weapons practice in Iwama, between 1942 and the end of the 1960s, should not obscure the fact that weapons were omnipresent in this 'original Aikido ’ that you mention. And Master Saito never claimed any originality for the aiki-ken and aiki-jo techniques of his method, which he said were only O Sensei's teaching. Indeed, the method created by Saito must not be confused with the techniques that this method organises, which are those of Morihei Ueshiba.

So, as a precaution, if not out of humility Leo, it would perhaps be wise to content ourselves with the Aikido discovered by O Sensei, rather than constructing a personal interpretation based on the disparate and fragmentary elements that are yours in a research that the Founder already brought to a brilliant conclusion.

To put it another way, Aikido is complete: it is not Aikido that can evolve, but the people who practise it. So neither youth nor old age are "at the service of the evolution of Aikido", as you think, but Aikido is at the service of the evolution of human beings, provided they are willing to work with a minimum of humility. So be careful not to try to evolve an art that reached maturity long before you were born, because the only possible evolution for a ripe fruit is to rot.

As Clémenceau, Pierre Dac and then Coluche used to say, the more you pedal slower the less you go faster, and I can't help adding: especially if you pedal at the side of the bike.

It's not boring chatting with you, my friends, but the best things come to an end, and happily so do the worst, and if I've offended anyone I apologise and put the words back in my bag. You have to know when to walk away from the table.

Thank you Guillaume, thank you Leo, for the chat around the stove.

As I leave the pub, I think of the whirlwind of life, the mischievous whirlwind of yin and yang, which makes it possible for a seductive face to conceal an imposture, and conversely for sincerity to sometimes hide behind an ugly mask. Dorian Gray is not far off, ‘I is another’, people are not what they appear to be. But there comes a time when masks come off, all masks.

Thinking of you

Philippe Voarino, 31 October 2020 for the French version